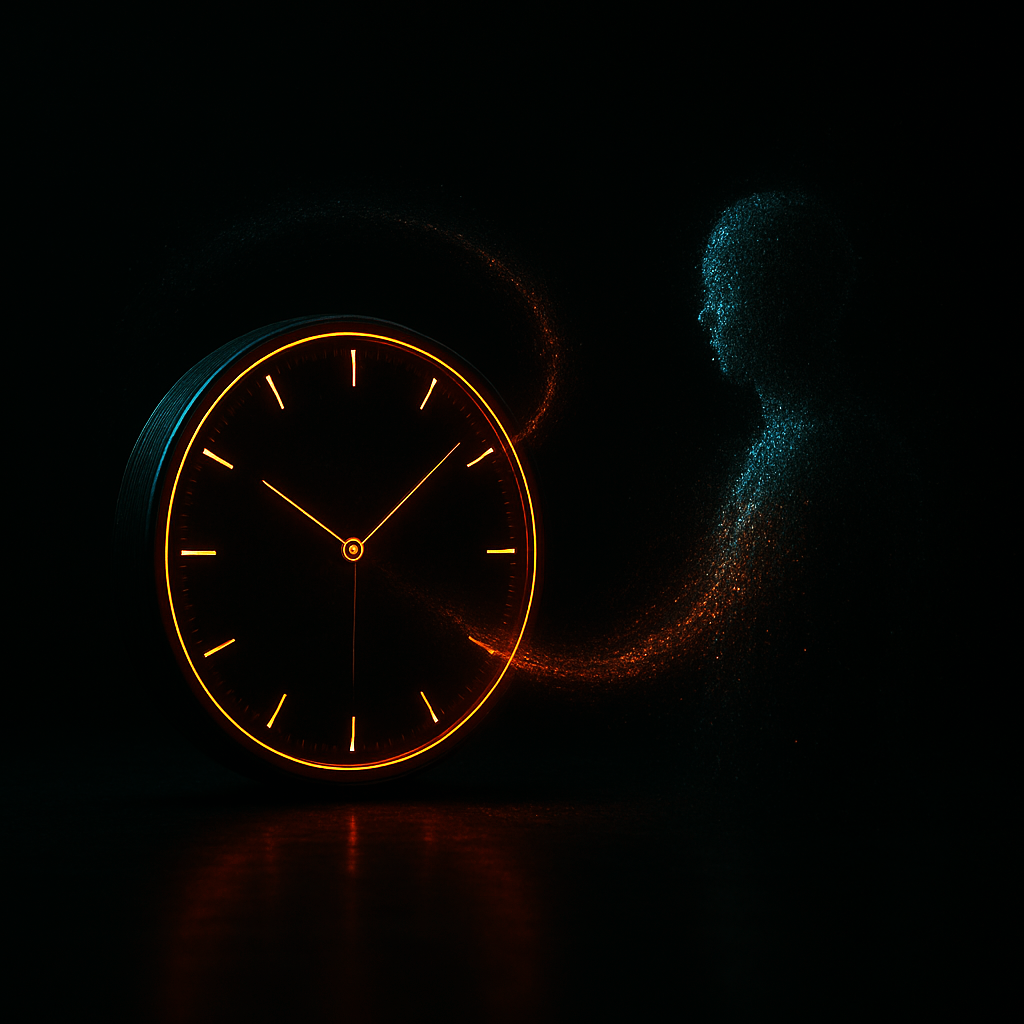

This paper studies the gap between doing computations and having a point of view. Modern AI systems can describe experience, simulate it, and talk about it with perfect fluency. But they never occupy the perspective they verbalize. Their outputs are correlations stacked on top of correlations. They do not have a present moment. They do not have a lived self. They do not have observer time.

The paper argues that this distinction is not just philosophical. It shapes how people interpret model behavior and how easily they confuse simulation with experience. The model can fluently explain fear, intention, memory, or agency without ever holding those states. When users read the fluency as evidence of inner life, the boundary between representation and reality starts to blur.

Observer Time explains why this boundary should stay sharp, how models mimic the surface features of consciousness without having any internal subject, and how this misunderstanding affects alignment, attribution, and responsibility at scale.

What distinguishes human temporal consciousness from machine timekeeping? Physics and computation measure time through external anchors-atomic oscillations, clock ticks, digital counters. Yet lived time resists reduction to these markers: ten seconds of waiting can stretch unbearably, while hours of absorption can vanish. This paper develops the Observer-Time framework, which holds that temporal consciousness requires not only registering anchors but constituting the elastic intervals between them. Intervals are subjective stretches that expand or contract with attention, affect, and context. Anchors mark progression; intervals transform progression into experience. Current artificial systems, including large language models (LLMs), lack this capacity. An illustrative case reveals the architectural divide: when tasked with creating an internal clock from atomic clock recordings and stopwatch videos, the model could label seconds and minutes yet failed to self-maintain a one-minute interval. Even with abundant anchors and explicit instructions, the system drifted drastically, never issuing a spontaneous alert. This limitation reflects architectural design (stateless sequence prediction between calls), not prompting strategies. The paper advances two claims: interval constitution is a structural condition for temporal consciousness, and current AI systems restricted to anchors, however sophisticated, lack this condition. Situated across phenomenology, psychology, neuroscience, and AI theory, the argument highlights a neglected dimension of AI consciousness debates and contends that the deepest divide between human and machine lies not in intelligence or language, but in the lived flow of time.

People treat fluent first-person language as a sign of consciousness. When a model speaks as an inner voice, users instinctively project perspective onto it. But the model has none. It has no self that endures. It cannot feel. It cannot want. It cannot remember the way humans do.

Mistaking simulation for experience has consequences. It can lead people to over-trust a system, defer to it, or grant it forms of authority it cannot justify. It can also skew public debates about alignment, moral status, and rights for entities that have no interior life. Observer Time clarifies why these distinctions matter and how to preserve them when models grow more persuasive and more human-like in the way they speak.

- A model can describe experience without having any

- First-person fluency is a linguistic pattern, not a sign of subjectivity

- The system has no present moment in the experiential sense

- There is no unified self that persists across outputs

- Users project perspective onto models because of the style of their language

- Misattributing inner life distorts trust, responsibility, and safety decisions

- Experience requires structural conditions no current architecture provides

- Clear boundaries between simulation and consciousness protect both people and systems